I’ve never been a fan of making a cold, hard distinction between extroverts and introverts.

I’ve never been a fan of making a cold, hard distinction between extroverts and introverts.

Although I myself identify as an extrovert because I draw energy from others, I wouldn’t say I possess every quality typical of an extrovert. I’d guess that if I surveyed our readers, most of you would say you’re somewhere in between the two.

You’re not alone. Most people fall somewhere on a spectrum, and there’s even a word it: ambiversion.

Some of you may have heard of ambiversion before. I hadn’t until very recently, when our CEO Brian Halligan mentioned it in his INBOUND 2014 keynote. After doing a little research, I found out that I probably am one — and you might be, too.

What Is Ambiversion?

Popular personality tests like Myers-Briggs polarize introversion and extroversion, making them seem like opposite and mutually exclusive categories. But in real life, people don’t often fit so squarely in those categories. I bet you know an introvert with an expansive networks of friends, or an extrovert who posesses an overwhelming fear of public speaking, even in front of a handful of people.

Put simply, ambiversion is a combination of introversion and extroversion. The word "ambivert" is defined in the Merrian-Webster dictionary as "a person having characteristics of both extrovert and introvert." In other words, they fall somewhere in the middle of the spectrum. The term itself isn’t new: It was coined in 1927 by social psychologist Kimball Young in Source Book for Social Psychology.

So, to understand ambiversion better, we need to understand introversion and extroversion. The most widely (though not necessarily universally) accepted distinction between the two has to do with the environment in which a person draws energy: Introverts tend to recharge by spending time alone, while extroverts recharge by spending time with other people. The exact reasons for these differences have long been debated — one study suggests extroverts have a chronically lower level of arousal, while another links the difference to dopamine levels in the brain.

According to the Washington Times, ambiverts have personality traits, likes, and dislikes associated with both extroverts and introverts. They are "socially comfortable and interactive, yet relish ‘down time alone’ more than extroverts and less than introverts. An ambivert can flow between both worlds with equal comfort, but not remain in others’ company too long."

Truthfully, a lot of us probably identify as ambiverts. It allows those of us who are "somewhere in between" to not commit to a label that has been given a distinct reputation over time. It recognizes that many of the stereotypes tacked on to the "introversion" and "extroversion" labels — for example, that extroverts like to be the center of attention and introverts are shy — are really just tendencies; they’re traits that are associated with, but not definitive of, one or the other.

While this may feel like we’re just arguing semantics, your personality type can affect one very important part of your life: your work.

How Does Ambiversion Affect Your Work?

Are introverts or extroverts smarter? More successful? Easier to work with? These questions are subjects of countless blog posts, newspaper articles, even books — all of which have contributed to the terms’ polarization. These sources all seem to focus on the working habits of the extreme personality types. But what about ambiverts, those who identify as somewhere between the two — how do they stack up in the workplace?

If I were to ask you which personality type is more successful, most of you would probably say extrovert. "These wonderfully gregarious folks, we like to think, have the right stuff for the role," writes Dan Pink, author of To Sell Is Human, in an article on the Washington Post. "They’re at ease in social settings. They know how to strike up conversations. They don’t shrink from making requests." All great qualities for being in business … right?

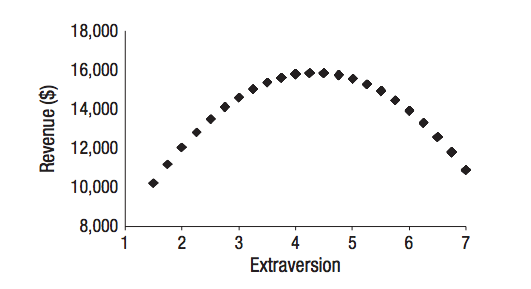

Adam Grant, a tenured professor at the Wharton School of Business of the University of Pennsylvania, challenged the assumption that extroverts make the best salespeople in his study, where he surveyed and collected three months of sales records for over 300 salespeople. What he found was that, on a scale from one to seven (one and two being least extroverted; six and seven being extremely introverted), people who were right in the middle — the threes, fours, and fives — brought in the most sales revenue over three months:

In other words, the most productive salespeople are neither low nor high in extroversion — they’re ambiverts. In that three month period, ambiverts made 24% more in sales revenue than introverts and 32% more in revenue than extroverts.

Grant theorizes: "It is possible [this] is explained by a positive effect of enthusiasm at low and moderate levels of extroversion, which is outweighed by the negative effect of assertiveness at high levels of extroversion." Another study will be needed to test this hypothesis, he adds.

Pink warns that people who fall on the high extrovert side of the spectrum — sixes and sevens on Grant’s scale — tend to "talk too much and listen too little. They can overwhelm others with the force of their personalities. Sometimes they care too deeply about being liked and not enough about getting tough things done."

Alright, so what about introverts? "They can be too shy to initiate, too skittish to deliver unpleasant news, and too timid to close the deal," says Pink. Like many things in life, moderation is best: The most productive people are well-rounded with qualities of both ends of the spectrum.

That’s good news for many of us. Although it seems to be popular nowadays to compare introverts and extroverts like apples to oranges, there is much more of a grey area between the two than many people realize. Eric Ravenscraft says it well: "The absolute worst thing you can do with either type is use a single word to define your approach." (So, naturally, someone came up with a single word to describe the ambiguous mixture of introversion and extroversion.)

Image Credit: Adam Grant

![]()